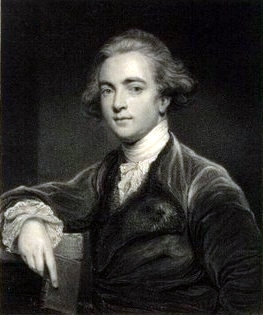

𝕊𝕚𝕣 𝕎𝕚𝕝𝕝𝕚𝕒𝕞: 𝕋𝕙𝕖 ℙ𝕖𝕣𝕤𝕚𝕒𝕟, 𝕆𝕣𝕚𝕖𝕟𝕥𝕒𝕝𝕚𝕤𝕥, 𝕒𝕟𝕕 𝕃𝕚𝕟𝕘𝕦𝕚𝕤𝕥 𝕁𝕠𝕟𝕖𝕤

A discovery announced 237 years back this week was the key that unlocked the connected ancient history of Indians, Persians, Europeans, and others who constitute 46% of humanity. The discovery led to a long, ongoing quest that has involved linguists, mythologists, anthropologists, archeologists, and — of late — geneticists. The man behind that discovery was an Anglo-Welsh polymath, Sir William Jones, a judge in British India and the founder of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Sir William said at a meeting of that society on Feb 2, 1786:

"The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family."

Jones was not the first to observe the family resemblance between Sanskrit and the languages of ancient Europe. He was also not the first to use the term Indo-European; it was the British scientist and scholar Sir Thomas Young who did that in 1813. And it was Germany's Franz Bopp who scientifically validated the affinity between Greek, Latin, Sanskrit, and Persian in 1816. Yet it's Jones who is usually — and, as we will see, justly — gets the credit for founding the field of Indo-European studies.

How Sir William Jones came to discover the Indo-European language family is a fascinating story. He was the son of a well-known mathematician, the senior William Jones. Father Jones was a close friend of Sir Isaac Newton and had come up with the idea of using the symbol π for the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter. The junior Jones was a child prodigy who learned Greek, Latin, Persian, Hebrew, Arabic, and some Chinese when he was still quite young. By the end of his life, he spoke 28 languages with various degrees of fluency. The image below is that of his book on Persian grammar.

His father died when he was just three, so his early life was one of financial hardship. After attending Harrow School, he went on to receive an M.A. from the University of Oxford. The Oxford campus has a frieze honoring Jones that shows him sitting under a banana tree, taking notes as the Indian scholars explain the ancient texts to him. Later in his life, he wrote a book on Persian grammar under the pen name of Youns Uksfardi, "Jones of Oxford".

Oxford University Memorial to Sir William Jones

After he graduated from Oxford, he tutored the seven-year-old Lord Althorp, an ancestor of Princess Diana. He went on to study law and developed sympathies for the cause of American independence. He tried to help Benjamin Franklin find a solution that would avoid a war with Britain. Having failed in that quest, he left for India and got appointed as a minor judge at the British Supreme Court in Calcutta, Bengal, where he founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784 (images below: the society's 1828 building and 1905 logo).

Now the British wanted India's Muslim and Hindu communities to be governed by their respective laws, so they appointed advisory panels of Muslim and Hindu experts to help draft those laws. As a Supreme Court judge tasked with developing the legal code for Hindus, Jones learned Sanskrit so he could translate Manusmṛiti, an ancient Hindu legal text. He wanted to use it as a basis for the British colonial law for Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs. From there, he went on to translate important works of Sanskrit literature (e.g., Kālidāsa's play Śakuntalā) and write many books about the Subcontinent on such things as law, music, geography, and botany. He wrote on an amazingly wide range of subjects that also included politics, literature, and chess (including a famous poem about chess). His expertise in multiple Asian languages and cultures combined with a prolific literary output earned him the triple monikers of "Linguist Jones", "Persian Jones", and "Orientalist Jones". Hence the title of this article.

But William Jones remains a man of contradictions: He discovered the Indo-European language family but failed to recognize the relationship between Avestan and Sanskrit, the languages closest to each other in the entire IE language family. When his opinion was sought on a recent translation of the Avestan texts, he thought they were a forgery. (He also mistook Pahlavi for a Semitic language.) He erroneously included Egyptian, Chinese, and Japanese in the IE family but left out Hindi and the Slavic languages. He believed that "conquerors from other kingdoms" brought Sanskrit to North India, which then replaced India's "pure Hindi". So he could not grasp the Sanskrit-Hindi connection either. He had other odd ideas as well, e.g., how the Chinese and the South Americans are related to the Hindus. We may be appalled by these errors but the methodology of comparative linguistics was still in its infancy.

To us the idea of a Sanskrit-speakers' conquest of India may sound like the colonial-era "Aryan conquest" narrative. Indeed, some modern Indian scholars fault him for having helped advance the British colonial agenda. We need to keep in mind, though, that he was a British civil servant and a creature of his times. His literary works, legal opinions, and humanitarian causes suggest that he was a fan of India's culture and — at least as far as he viewed himself — a friend of its people. He (and his network) got the European scholars fired up about studying Sanskrit and comparative linguistics the way no one else had been able to before him. For example, Alexander Hamilton, who was a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (founded by Jones), was one of the very first Europeans to learn Sanskrit. He became Europe's first professor of Sanskrit and went on to teach Sanskrit to the majority of Europe's earliest would-be Sanskrit scholars.

If you're an American wondering if this Hamilton fellow bears any relationship to the American Founding father with the same name, they were cousins! If you're a non-American, you may be intrigued by the fact that the Founding Father Hamilton died in a duel at the hands of the then US Vice President! But that's a story for another day.

Jones died in Calcutta in 1794 at the age of 47 from an inflamed liver and is buried in South Park Street Cemetery, a protected heritage site where many notables – for example, son of the Novelist Charles Dickens – lie buried. Despite his errors and omissions, he became an important bridge between South Asia and the West. Both South Asia and the West were forever changed by his insights into the relationship between the languages of Europe and South Asia.

I'd like to end this article with a poem called Solima written by Jones based on the works of Arabic-language poets. He says it was "written in praise of an Arabian princess, who had built a caravansera with pleasant gardens, for the refreshment of travellers and pilgrims; an act of munificence not uncommon in Asia." Caravanseras are found in the desert areas of Asia and North Africa. They are inns for travelers with a courtyard in the center. Here's the poem:

The stranger and the pilgrim well know,

When the sky is dark, and the north-wind rages,

When the mothers leave their sucking infants,

When no moisture can be seen in the clouds,

That thou art bountiful to them as the spring,

That thou art their chief support,

That thou art a sun to them by day, and a moon in the cloudy night.

Suggested readings (all online):

- Jones, W (1786). The Third Anniversary Discourse, on the Hindus, delivered 2d of February, 1786. Read at the Electronic Library of Historiography website.

- Campbell, L (2018). "Why Sir William Jones Got It All Wrong, or Jones’ Role in How to Establish Language Families". Download PDF from the ResearchGate website.

- Read more of Sir William's translations of poems in various Asian languages: https://opus.bibliothek.uni-augsburg.de/opus4/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/1284/file/Jones_Poems_Beck_Edition.pdf

- If you'd like to dig into works by or on Sir William Jones, the Internet Archive offers a large collections.

.jpg)